Geistergegenwart, RAY Filmmagazin 12/23+01/24, pp.68-73

Text und Interview – Andreas Ungerböck, LINK

A comprehensive and detailed book review spanning six pages in Ray Filmmagazin.

Eine umfassende und detaillierte Buchrezension über sechs Seiten im Ray Filmmagazin.

Translation of the article:

Ghostly presence

11/2023 | Andreas Ungerböck | RAY Filmmagazine

A new book sheds light on Ella Raidel’s multi-award-winning film work. A conversation with the Upper Austrian artist and author, who has (also) lived in Asia for over two decades.

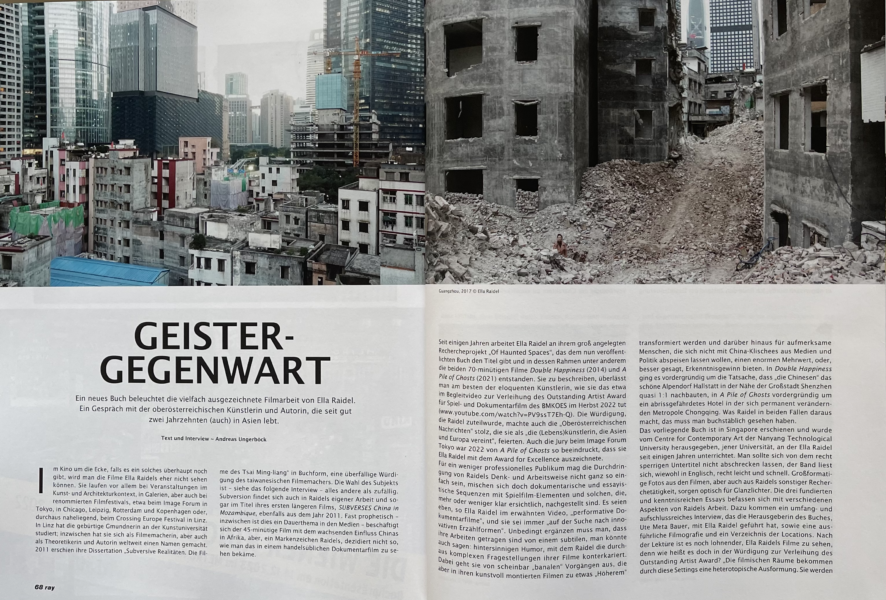

You are unlikely to see Ella Raidel’s films in the cinema around the corner, if there still is one. They are mainly shown at events in the art and architecture context, in galleries, but also at renowned film festivals, such as the Image Forum in Tokyo, Chicago, Leipzig, Rotterdam and Copenhagen or, quite obviously, at the Crossing Europe Festival in Linz. Born in Gmunden, she studied at the University of Art and Design in Linz and has since made a name for herself worldwide as a filmmaker, theorist and author. In 2011, she published her dissertation “Subversive Realities. The Films of Tsai Ming-liang” was published in book form in 2011, an overdue tribute to the Taiwanese filmmaker. The choice of subject – see the following interview – is anything but random. Subversion can also be found in Raidel’s own work and even in the title of her first longer film, SUBVERSES China in Mozambique, also from 2011. The 45-minute film deals almost prophetically with China’s growing influence in Africa – now a constant topic in the media – but, as is Raidel’s trademark, decidedly not in the way you would see it in a standard documentary film.

For several years, Ella Raidel has been working on her large-scale research project “Of Haunted Spaces”, which gives the now-published book its title and in the context of which the two 70-minute films Double Happiness (2014) and A Pile of Ghosts (2021) were made. It is best left to the eloquent artist to describe them, as she does in the video accompanying the BMKOES Outstanding Artist Award for feature and documentary film in autumn 2022 ( LINK). The honour bestowed on Raidel also made the “Oberösterreichische Nachrichten” newspaper proud, which celebrated her as “the (life) artist who unites Asia and Europe”. The jury at the Image Forum Tokyo in 2022 was also so impressed by A Pile of Ghosts that it honoured Ella Raidel with the Award for Excellence.

For a less professional audience, it may not be quite so easy to enter Raidel’s way of thinking and working, as documentary and essayistic sequences are mixed with feature film elements and those that are, more or less clearly, re-enacted. According to Ella Raidel in the aforementioned video, these are “performative documentary films”, and she is always “in search of innovative narrative forms”. It is important to add that her works are underpinned by subtle, one could also say subtle humour, which Raidel uses to counteract the thoroughly complex issues in her films.

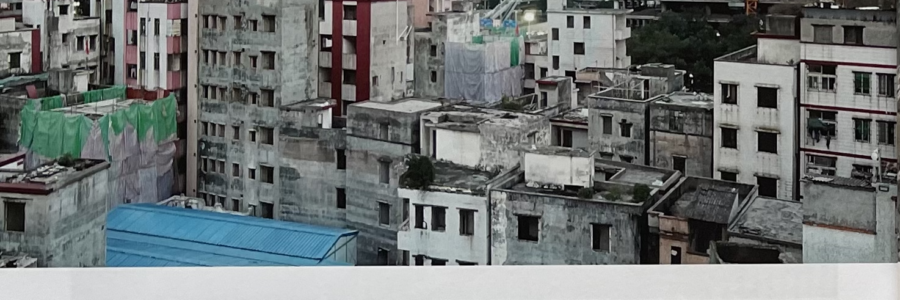

She starts from seemingly “banal” processes, which are transformed into something “higher” in her artfully assembled films and offer enormous added value, or rather, a gain in knowledge, for attentive people who do not want to be fobbed off with China clichés from the media and politics. Double Happiness is ostensibly about the fact that “the Chinese” recreated the beautiful Alpine village of Hallstatt near the city of Shenzhen almost 1:1, while A Pile of Ghosts is ostensibly about a hotel in danger of demolition in the constantly changing metropolis of Chongqing. What Raidel makes of it in both cases literally has to be seen to be believed.

This book was published in Singapore by the NTUCCA Centre for Contemporary Art at Nanyang Technological University, the university where Ella Raidel has been teaching for several years. One should not be put off by the rather unwieldy subtitle; the volume, although in English, reads quite easily and quickly. Large-format photos from the films, but also from Raidel’s other research activities, provide visual highlights. The three well-founded and knowledgeable essays deal with various aspects of Raidel’s work. There is also an extensive and informative interview with Ella Raidel conducted by the book’s editor, Ute Meta Bauer, as well as a detailed filmography and a list of locations. After reading the book, it is even more rewarding to watch Ella Raidel’s films because, as it says in the tribute to the Outstanding Artist Award: “The filmic spaces take on a heterotopic form through these settings. They become stages and picture puzzles that can no longer be clearly categorized. Personal narratives of people, commentaries and historical references merge ontologically with the architecture to form a mental image. The result is a new, open cinema.” There’s no better way to put it, at best, more simply.

INTERVIEW

AU: Where does your interest, your fascination for the Chinese-speaking world come from?

Ella Raidel: It stems from my enthusiasm for cinema. In the nineties, I was fascinated by the films of Wong Kar Wai and later by the Taiwanese New Wave. I was living in Berlin at the time, and there were retrospectives of Ang Lee and Tsai Ming-liang. Tsai’s The River (1997) was shown in the cinema. The slowness of the images had an incredible pull on me. It felt like I was in a trance. The River begins with a scene where you watch the father smoking for several minutes, and nothing else happens. The image section towards the open window suggests the city through its sounds without you seeing it. You listen to the images.

I had planned a trip to Taipei and wanted to know what it was like there. It was only later that I realised that in Tsai Ming-liang’s films, you almost never get to see anything of the city and only spend time in cubic interiors, passageways or passages. One of the few films in which Taipei can be seen is the short film The Skywalk is Gone (2002), still one of my favourites. The film shows Chen Shiang-chyi returning to Taipei after a trip to Paris and being unable to find the passage to the main station because it has been demolished. I think the state of disorientation caused by rapid urbanisation is very apt. In Chinese-language cinema, this means not only being lost in the city, but also having lost touch with history and belonging.

My film A Pile of Ghosts is also about this disorientation caused by rapid urbanisation through Chinese ghost towns, i.e. towns that are built but not inhabited by anyone. In one area, an entire neighbourhood is demolished, leaving a hotel owner in ruins who is haunted by the vacancy, the social upheaval and a Hollywood film. “A bunch of ghosts” in the film refers to the haunting that spreads through speculation with the infrastructure.

AU: You have written a book about Tsai Ming-liang. How does your work relate to his?

Ella Raidel: Tsai Ming-liang was my introduction to Taiwan and, in a way, to my exploration of Asian cinema in general. As I said, I found the films aesthetically interesting, the composition of the images, the length of the shots, the sound design and, of course, the themes, which deal in many ways with the upheaval of a society shaped by Confucianism. I think all his films are great, and having studied his films and the context of Chinese-language cinema very intensively, this has certainly had an impact on my films. For example, conceiving a documentary film as a musical, incorporating performative scenes as commentary, and understanding acting as performance, not so much as acting. Developing a psychology of the characters in relation to the urban environment, for example, walking through ruins, spaces and cities. By wandering around, I find it particularly beautiful to sharpen an eye that allows us to look around us in the present and thus open up spaces of thought that need no explanation. Tsai Ming-liang comes from Malaysia, his family from generations of migration stories from Guangzhou, today he lives in Taiwan. For me, his background is characteristic of a culture that emerged outside China through migration. That’s probably why my research into Chinese-language cinema led me to Singapore, where diverse cultures with different migration histories live.

AU: You have been teaching at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore for several years. What exactly do you do there, and how do you perceive your work with the students? What about the so-called “cultural differences”?

Ella Raidel: Having been in Asia for more than 20 years, I don’t see any cultural distance. The distance has become a closeness because the culture is very familiar to me. My research and films are all about this part of the world. I teach film and extended film formats that move between fiction and documentary – performative interventions as a method and filmmaking as artistic research – and think about the future of cinema. I am currently working on new audiovisual formats, immersive storytelling, 360-degree film and the use of new technologies. The future of cinema is characterised by a shift from traditional cinema to a wide range of new and experimental practices that signify its own future in visual storytelling. Accompanied by recent technological advances and the changing media environment, the cinema of the future is transforming from simply watching films to an experience of “touching”, “listening”, “participating”, “engaging”, “performing”, and “sharing” the image content, creating an alternative sensory mode. The cinema of the future also points to the fact that films are no longer only shown in cinemas but can be found in different places: on computer screens, at exhibitions in galleries, in immersive theatre, in concert halls, with VR glasses, in public places and even in people’s own living rooms – this, in turn, determines the social relationships within the viewing communities. The development of moving image narrative art is changing the way we see and live.

AU: How did you become interested in the Chinese influence in Africa, which is a major topic in the media today, very early on, in 2010?

Ella Raidel: My interest in a topic or country always starts with cinema, for example, Mozambique. I was invited with a group of filmmakers from the IFFR International Film Festival in Rotterdam on a research trip to sub-Saharan Africa for a programme entitled Forget Africa. I chose Mozambique because I had read that Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville had worked there on their Sonimage project in the seventies. I followed this trail but then focussed on other topics during the course of the trip, namely the Chinese infrastructure projects in Maputo. China’s economic and infrastructural measures in Africa thus became the subject of my film SUBVERSES China in Mozambique.

“Sub-Verses” is both a pun on the term “verse” – that of the slam poetry being performed – and the subversive effect of its performance. While working on Slam Video Maputo (2009), I saw Chinese construction workers on the streets who locals said were prisoners from China. I later returned for a second visit to research and shoot SUBVERSES China in Mozambique. This time I investigated China’s economic involvement and presence in Africa, which manifested itself in infrastructure projects such as a new airport in Maputo, government buildings, a football stadium, bridges and roads. In this film, I began to include poetry, songs and advertising copy as sub-verses to the dominant narratives. I combined observational footage and documentary, interrupted and intersected by performative actions.

AU: There is a strange mixture of fascination and disgust about the People’s Republic of China in current discussions and also in politics. How do you see that?

Ella Raidel: China is the great unknown. When people ask me questions after my film screenings, I often notice that there is little knowledge about the country and many prejudices. In recent decades, China has managed to transform itself from an agrarian society into an urban society. With a population of billions, this process is huge and has been reflected in the urbanisation process that interests me. The infrastructure projects have also created jobs and boosted the economy, resulting in an overproduction of infrastructure. Countless cities have been built that will never be inhabited. For me, these are the “haunted spaces”, the haunted places where capital exerts its own effect. The image of empty urban ruins may be fascinating and alarming, as we are rapidly moving towards a collapse of the ecological system, to which urbanisation, a useless one at that, has also contributed.

AU: Two terms in your book describe your films very well: “reality fiction” and “documentary melodrama.” Can you explain them a little?

Ella Raidel: In my films, I am always looking for new narrative styles. References often come from pop culture, Hollywood or the media in general. For example, in my first film Slam Video Maputo, I use slam poetry as commentary and the making of music videos as a self-referential narrative form. I have developed this further in all my other films. I often look behind the scenes of film productions as a commentary on our time, in which everything is manipulated by the media. We live in a “reality fiction” in which our roles are prescribed like film scripts. The melodrama was added as an indication of how strongly Hollywood cinema influences our reality. In the case of China, it was old Hollywood films like Sound Of Music (1965), Casablanca (1942) or Waterloo Bridge (1940) and the melodramatic plots that opened the door to the West. That’s why I conceived my films in reference to or as quotations from these films. My documentary films can be read as implied melodramas because the properties are always about the dream and trauma of living together.

AU:Is the impression correct that your work is increasingly moving away from documentary films towards fiction films? What role does the fictional play in your considerations?

Ella Raidel: I have never seen myself as a documentary filmmaker, let alone a “classic” one. Because I’ve always questioned the narratives in documentary films. At the end of the day, it’s just a film that has been constructed through montage. I come more from the visual arts or media art, my films are documentary, performative, hybrid. Above all, I want my films to open up a space for thought that allows people to think for themselves through images and sound. Documentary film is a great format that allows a lot of artistic freedom. For me, however, it is above all a tool for thinking along the lines of film. It’s about exploring a topic on film, in my case it’s the Chinese ghost towns or the urbanisation of China in general. I approach the subject step by step; I see my films as research.

Fiction plays with reality. In A Pile of Ghosts, I have a protagonist called Charles. He lives in a ruin in Chongqing and would like to be an actor. So he plays himself in a role of his own choosing. We go out on the street with him, filming how he interacts with passers-by. I arrange a documentary theatre on the street. In this way, I see the staging for the documentary film as a game with reality. In the end, it’s neither a documentary nor a feature film. That’s the beauty of playing, it’s a way of trying something out.

AU: For an “untrained” audience, it may be difficult to distinguish between what is documentary and what is fictional. Is this an issue for you, or should people be “challenged”?

Ella Raidel: For an “untrained” audience, Tsai Ming-liang’s films are also an imposition. You can’t please everyone, and yet many others like it. As my films are usually shown at film festivals or exhibitions, there is usually an audience that at least dares to approach this hybrid format.

AU: One point rightly emphasised in the book is the precision of your work and images. How do you prepare and shoot? Is there a fixed concept, or do you deviate from it when you realise something interesting that is not planned?

Ella Raidel: I see myself as a photographer and have always been interested in architecture and architectural photography. On my research trips, I photograph and shoot myself. That’s how I take my first pictures, and because I do it alone, I’ve got into the habit of always using a tripod. As a result, my pictures look very precise in terms of composition, and my films look like photographic tableaux. I usually travel to places that are completely new to me. And as I said, the film is created along the way as research, which is also like a search for the film script. I can’t foresee and plan everything I’m going to shoot, and a lot depends on chance on location. I have developed some improvisation techniques for this. As I mentioned earlier, playing with reality as a theatre in situ. There are a lot of photos in the book that were taken on these research trips and are not shown in the films, so I’m pleased that I’ve now published them.

AU: What is the “Of Haunted Spaces” project all about? Can you already foresee how it will continue, or is there something like an “end goal”?

Ella Raidel: “Of Haunted Spaces” is based on my interest in urbanisation and infrastructure projects in China and beyond. I have visited countless areas all over China, abandoned holiday resorts on the east coast of Shandong province or the New Lanzhou area in Gansu province, the beginning of the old Silk Road, where hundreds of mountains have been levelled to build a new city. Each of these newly developed areas has a theme park to promote the construction project. The replicas from all parts of the world stand as monuments to speculation, accelerated by global capitalism. China has expanded its presence and influence from Africa to many other countries through the Silk Road project, and many of these countries are heavily indebted. The entire property industry in China has collapsed, it couldn’t be otherwise with these gigantic dimensions, with such a massive impact on nature and the environment. The book documents my work on this topic and on the three films that were made. China has expanded its territory globally, so it remains to be seen what will happen next. The book therefore marks a stage.

AU: In very practical terms, How will the construction boom in China continue? Is there any change in sight, also in view of the recent property crisis?

Ella Raidel: In many of my discussions with experts, people doubted that there could ever be a property crisis. It was expected that China would be able to support itself within its system. But if you take a closer look, as my book shows, it couldn’t have turned out any other way. “Of Haunted Spaces” are the haunted places of speculation where people were led to believe in a promise of profit and a prosperous future with advertising slogans. In China, Africa and along the New Silk Road, there are now countless privately indebted people and entire countries that have been blinded by these investments.